THOUGHTS, IDEAS, QUESTIONS, PROCESS, LESSONS,

Student Post

FWEEK 3 – LAUGH WHEN YOU LAUGH

OSHOW – Week 3

Week 3

This time, at Shawn’s suggestion, I will try to write an article in an interview format, with “O” being me, (OSHOW), and “S” being my other self (Shota).

I will write the article as a dialogue between the two of us. It’s kind of like Stanislavsky’s “An Actor Prepares”.

S: How do you feel after spending three weeks here?

O: I’ve gotten used to life and have found my rhythm. It is as comfortable as ever, but sometimes I am surprised at how cold it gets. But basically, the weather is good, so I spend a lot of time outside. I go shopping even on ordinary days, and we often have classes outside, and I like that time. I went shopping the other day and bought a notebook. I have a notebook to write down my daily records, but I haven’t done so much to summarize my thoughts, come to think of it, so I decided to start little by little. I wouldn’t be ashamed of if it was published in book form and passed on to someone else.

O: I’ve gotten used to life and have found my rhythm. It is as comfortable as ever, but sometimes I am surprised at how cold it gets. But basically, the weather is good, so I spend a lot of time outside. I go shopping even on ordinary days, and we often have classes outside, and I like that time. I went shopping the other day and bought a notebook. I have a notebook to write down my daily records, but I haven’t done so much to summarize my thoughts, come to think of it, so I decided to start little by little. I wouldn’t be ashamed of if it was published in book form and passed on to someone else.

S: Do you have anything new to add to the notebook after coming here?

O: There are many things. First of all, I might write about how to divide spirit and technique. I was especially happy to see the division between clowning and storytelling. I like clowning.

Shawn was surprised when I told him that there are almost no clowning workshops in Japan. I think it’s something Japanese people need and they are very talented in clowning. They are all cute and vulnerable, and when I perform overseas, I feel that people like me more than I think they do. I think that is a big advantage. I think Japanese people should know that they can make the most of their talent. I think there is a difference between a good improviser and a skillful improviser, but I feel like everyone is trying to be a skillful improviser. Everyone tries to learn techniques and theories, but in my opinion, it is better to improve the spirit, especially in the beginning. Because the more experience you gain, the harder it is to refine your spirits.

Just as adults are more stubborn than children about change, it is harder to let go of experiences than to cultivate them. That’s why I think it’s better to learn how to let go first. Skills and experience are acquired on their own as long as you do it.

…as adults are more stubborn than children about change, it is harder to let go of experiences than to cultivate them

S: You often led young teams, but you didn’t mention much about technique, didn’t you?

O:Yes. I wanted to bring up people who would be wonderful just by standing on stage. But now that I’m here, I feel the importance of storytelling more. Especially Keith Johnstone’s storytelling (Platform→Tilt→Reincorporation) is simple but profound and interesting. When you get into this properly, it makes for a great scene. But even in a Loose Moose show, there are only one or two such scenes per show.

They run away to verbal expressions and hesitate in the face of risk. There are 17 techniques to kill a story, and they happen at certain points. I thought Keith was a genius for coming up with that.

S: Are there any differences between Japanese and Canadian shows?

O: The biggest difference is the quality of the players.

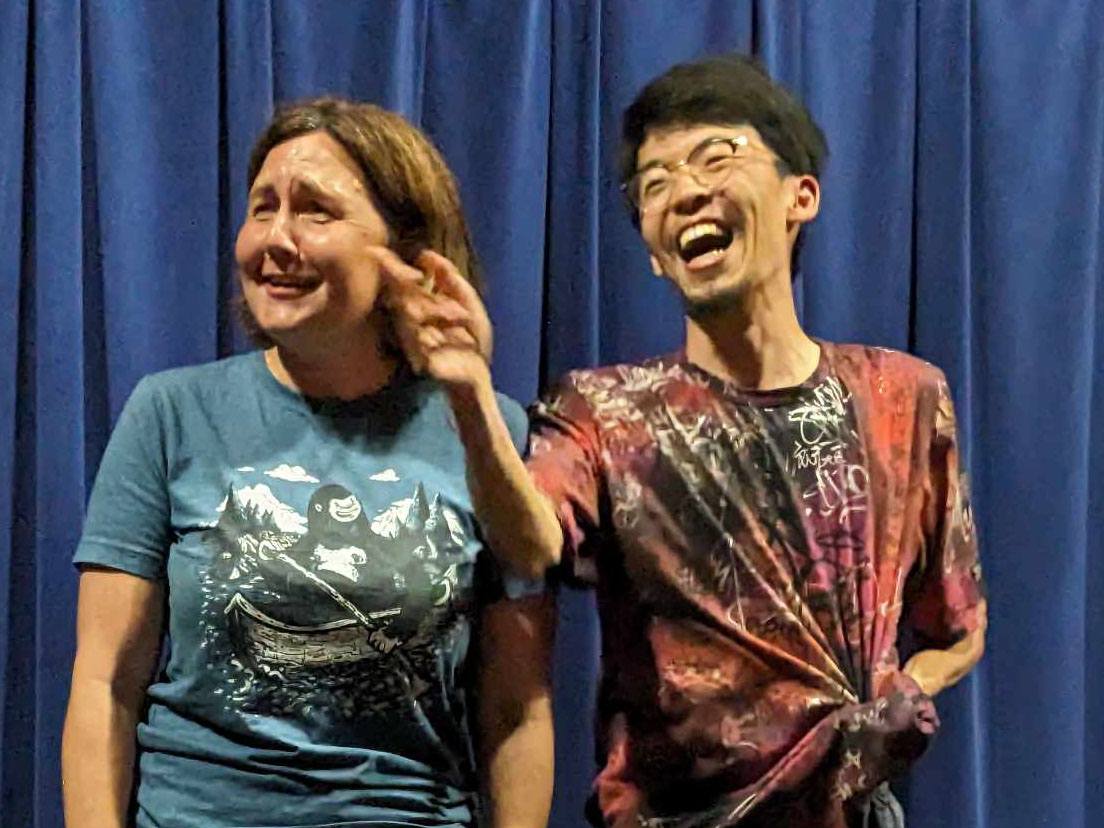

(Photo Cindy Pittens – Oshow and Alice at the Loose Moose Theatre)

Many players here are energetic, but in Japan they are quiet and polite. I think it would be perfect if about half of them were in Maestro.

I have the impression that there are almost no misbehaving players in Japan. I think I’m the type of person who likes to misbehave a lot, but I think I probably wouldn’t stand out over here. There is the problem of language, but I think players here are more bold.

The audience is also different. There are more enthusiastic people here, and it is easier for the audience to become one. I think it’s a comfortable space for players, but at the same time it can be dangerous. If the audience likes a crappy scene, it can get a high score. Loose Moose players don’t want that, but their enthusiasm can control the show.

It is the job of the improviser to tame this huge monster.

I have the impression that Japanese audiences are very individualistic. And since the scores are given honestly, the show is not controlled to a large extent. I think it is quite easy to control them. But for that, I think the storytelling of the improviser needs to grow.

Quiet and heartwarming scenes are quite popular in Japan. This is a good thing, but also dangerous. These scenes don’t move the story forward much, which means there is no risk. They are certainly pleasant to watch, but they are not exciting.

Full-length Impro, a type of long-form impro, is becoming popular in the Japanese impro scene, but I think it suffers from the same problem. Well, I introduced it, but I think it has been somewhat misunderstood and misrepresented. Anyway, I feel that the need for storytelling skills exists in both countries, but for different reasons.

S: What are the problems that full-length Impro faces?

O: I may have talked about this before, but in many cases, the story of so-called long-form impro often dies. The point is that because the show is done for a long time, what needs to be done now doesn’t need to be done now. This causes the story to be delayed or scattered, and that tends to happen quite often.

Incidentally, long form and full-length impro are strictly different things: long form is a long form with a comedy-based structure that originated in Chicago, and full-length is a theater-based work without a structure that was developed by BATS, Impro Theatre, and others. I believe the latter is derived from Keith Johnstone’s narrative impro.

In other words, all good full-length improvisers are well trained in Keith Johnstone’s improv. We should not forget this. But in Japan, (and I think this is one of the problems of Japanese impro education), people try full-length impro without learning Keith’s impro that well. It may be possible to run for a long time if you get used to it, but this is just getting used to it, and whether or not you can create an interesting piece is another thing.

Jun Imai said, “Unless you can make a solid short scene, you will be bored even if you do a long one,” and I really think that is true. Well, I think Jun is exploring the same problem now.

S: What do you think are the problems of impro education in Japan?

O: First of all, there are not enough proper teachers. I don’t think more than half of the people teaching have studied Keith’s impro properly. Even if they have, it is only a little bit, or they have learned it, but they have not mastered it. This is very obvious when you watch the scenes they create.

The problem is that there are not many people in the older generation who can properly teach Keith’s impro. The only ones I can think of are Jun Imai and Takashi Takao, and Jun is no longer teaching Keith’s impro classes. The only people who have been lucky enough to learn from them are those who have studied abroad, so there are really very few of them. And the other thing is that there is no place to learn impro step by step.

There are many workshops where you can try impro, but there are not many places that will teach you how to get better at it and let you experience shows. So we have no choice but to do shows by ourselves or go to workshops here and there.

I think Loose Moose has a good system in that sense. That is why graduates of Loose Moose are active all over the world with Keith’s impro as their common language. And when they come back, they can support the show as excellent veteran players. I used to have a group that could do that, but I quit. Now I’m thinking about starting over again, but again, I think this is something I need to do.

S: Let’s go back to Shawn’s class. Have you had any difficulties in your classes?

O: I thought it was inevitable that I would run into language problems, but then I got more and more used to it and started to feel like I wanted to do well. This is really disturbing. When this is clinging to me, spirits are neglected.

Fear of failure prevents us from taking on bold challenges.

I feel like I am growing while adjusting to the balance between the two. I think this will continue forever. But I think it’s good that I am able to do this without stress. Shawn reminds me of that all the time. He’s the most playful person in the class, and I respect that.

S: In this week’s show, you saw a female player named Laura who is a maestro.

O: She was a very bold and nice player. I don’t see that type of person in Japan, someone that bold. She danced sexy on stage, provoked the director, but she was also very sensitive and responsive to her partner, and was well-liked. There is an Israeli player named Inbal Lori, and I think she is another example of a bold female player.

I talked with Shawn after the show, and we agreed that it is important to train female players like that in Japan. I heard that there was once a Japanese female player who came to Loose Moose who was quiet during the beginning of workshops, but as time passed, she became very sexy and bold in class and on stage. But when Shawn went to Japan for a workshop, he saw her again, and she was back to being a quiet woman. Shawn asked, “Where did that bold girl go?”, and she said “I can’t do that in Japan…”. I think it’s a shame.

Gender issues are often discussed in the impro world today, but I think it’s important that there are bold female players out there. When discussing gender diversity, masculinity and femininity are sometimes treated negatively, but I think that is the exact opposite of diversity. I think the goal of diversity is for everyone to be indifferent in a positive way, to say, “Oh, so that’s who you are, I see” I think it’s different to deny existing masculinity and femininity.

My mother, in particular, was a professional club owner-mom, which is a feminine occupation, and she was very confident and proud of her sexuality. So I think it is important to make full use of one’s sexuality. But in Japan, wearing revealing clothes is considered immodest, and asking for it is treated as sexual harassment. I have a friend who is a drag queen, and she is really nice, beautiful, and smart. And I think there should be more performers like that.

I really hope that the world will be a place where people can shine and respect each other for who they are.

S: Finally, how do you want to spend the rest of your time?

O: I think I’m going to give up on languages. I would rather make the most of my clown states and the goodness of my way of being. I think I can use this in my performances after I return to Japan. Because of the language barrier and the fact that I can’t do scenes well, many things become risky. I think this is a big advantage. You may feel somewhat embarrassed about not being able to speak the language, but you may say, “I don’t care about that! Laugh when you laugh!”.

By the way, as a teacher, I’ve gained a lot of confidence. People are happy with what I offer, and Shawn’s feedback and comments are often helpful and encouraging. And it’s great to see Shawn’s teaching style.

Lately I’ve been going to classes thinking about what it would be like to be in Shawn’s shoes. If I were in Shawn’s shoes, I would say, “I wouldn’t make this comment here,” or “I wouldn’t stop here”. I don’t know which is the right answer, but I like to compare and contrast. I’ll be at the show next week, and there’s still a lot to look forward to!

“Laugh when you laugh!”

Photo- Cindy Pittens. Alice and Oshow at the Loose Moose

0 Comments